The learned have said

'Mokshaika Hetu Vidyā Śreevidyāiva Na Samshaya:'

The wants of human beings are many. The most common among them is about salvation. Salvation means, getting rid of all the sorrows suffering presently and moving to the stage of Supreme Bliss. This has been clearly mentioned in Vedas. The evidences like Svetasvatara Upanishad (11-3,8) convey that self-realization is an important tool to this; Gnānādeva Tu Kaivalyam Tameva Viditvā Ati Mrutymeti. Still it is very difficult for everyone to get that self realization. That can be reached only by getting the Vedanta books like Upanishads, Śreemad Bhagavad Geeta, Sūtras of Vyāsa, and their commentaries, etc., hearing them read by teachers, thinking about them, and meditating on them. Further maturity, determination, control of organs, control of mind, passion, peace, patience, and interest on salvation are all very important. Getting eligible for this out of normal family life is very difficult.

For this purpose only, Vedas have prescribed the routes of worship (upāsana) and devotion for the medium level people. Because of this worship the mind becomes focused, get drenched in the benign look of good teachers, get the opportunity to hear Vedāntas in this birth itself and help to get salvation. It will not be a great loss for them, even if they do not get self realization in this birth itself. Because, after death, they reach the world of Brahma called Śreepuram. There they get taught the tattva by Sanaka and other sages and reach soul salvation early. Hence, they do not have re-birth again and enjoy the supreme form. This is the important usage of worship path. For those who do not follow this path, Vedas have prescribed the path of actions. That is, actions like Sandhyāvandanam, chanting of mantras (japa), homa (conducting sacrificial fires), doing poojas, Agnihotram, Chāturmāsya, Darsa, Vājapeyam, Ashvamedham, etc. Sastra says that for those who do these actions without specific interest on the results, but still do them only for satiating the Supreme Being, get their mind purified and enter into the worship path or the knowledge path, which is above it. Tametam Vedānuvachanenena… Vivitishanti. Brahadaranyaka Upanishad (44-22)

Vedas mention such worship in many ways. They are, Prateeka worship, Sampat worship and Aham Graham, etc. In the section of Veda called Aranyakam the methods of such worship have been clearly mentioned, the rules prescribed, the regulations to be followed, etc. They are mentioned in Upanishads also then and there.

Our ancestors and sages have all in general followed the worship path only. It was easy for them to follow the worship path because they have learnt the Vedas and have understood the meanings also. The worship method started to fade away on account of passage of time and since most of the people did not understand the meaning of Vedas. At this stage, the great incarnation Śree Ādi Śankara wanted to clearly show this path and have identified and evolved six important worshipping methods. That is why he got the title as Shanmatha Pratishtāpanāchāryar (establisher of six religions). Like him some more great people have also explained the worshipping methods. However, only the methods established by Śree Ādi Śaņkara prevail in this world. Those six methods are; Ganapatyam, Koumāram, Souram, Saivam, Vaishnavam andŚāktam.

For each of these, the Sūtras, commentaries, worshipping methods, etc., have been prescribed. The great persons like Śree Bhāskararāya, who came after Śree Adi Sankara have expanded these methods as easily understandable by all and followed the traditions.

The six methods mentioned above are all equal status. However, worshipping of Śreedevee has been considered as a great one and has been followed by many people right from early days. For Śree Adi Sankara also, internally liked path is worshipping of Śreedevee only. That is the reason, he has specifically mentioned in his commentaries on Śree Bhagavad Geeta as; ShaktiShaktimatoh abeda: This is clearly mentioned in the 14th chapter. Hence let us see some nuances about worshipping Śreedevee.

We read about worshipping Śreedevee in Veda and others. Rig Veda (5-47-4) says; Chatvāra Em Pipratikshemayanta: The verses beginning with Emanukam in Yajur Veda describe about Śreechakra and Kundalinee and other energies in our body. Many Upanishads forming part of Atharvana Veda like Tripuropanishad, Devee Upanishad, Tripuratāpinee Upanishad, Pāvanopanishad and Bahvrucha Upanishad explain worshipping Śreedevee. The books called tantras are in the form of discussions between Paramashiva and Śreedevee. They form the basis for this worship. There are 64 in number and the important among them are Tantra Rāja Tantram and Svatantra Tantram. These are must read books for all the worshippers.

Sūtras: The Sūtras which form the basis for Śreevidyā are all done by Parasurama. Hence they are called Parasurāma Kalpasūtras. It has 10 sections. The second section describes about worshipping Ganapati and all the other describe about worshipping Śreedevee. One famous Meemāsaka called Rameshwara Soori has written commentary for this in a convincing and clear way. His most liked disciple is our Śree Bhāskararāya.

Purānas: Śree Vyāsa has clearly shown in his purānas about the greatness of worshipping Śreedevee. Particular mention has to be made about Śreedevee Bhagavatam, Brahmanda Purānam, Märkandeya Purānam, Skanda Purānam and Padma Purāņam. The famous Durgā Saptashatee is a subset of Mārkandeya Purānam. The hymn Śree Lalitā Sahasranama forms part of Brahmanda Purana. Lalitopākhyāna explains in detail about the plays of Śreedevee like destruction of Bhandāsura.

Stotras: There are many verses describing the methods and greatness of worshipping Śreedevee. Important among them are; Śreeshubakotaya Stuti, Shakti Mahimnā Stotra authored by sage Doorvāsa, Durgāchandra Kalā Stotra, Soundaryalaharee authored by Śree Adi Šaņkara, Panchadasee Stotra and Tripurasundaree Mānasika Pooja.

The greatest among the worshippers of Śreevidyā, is Śree Parameshvara himself. Next in the order is Śree Hayagreeva, Agastya, Lopamudra, Indra, Kubera, Sun, Cupid, Kālidāsa, etc. It is understood that Śree Lalita Sahasranāma hymn was told to sage Agastya by Śree Hayagreeva. Parasurama and other incarnations also are worshippers of Śreedevee. In that process this worship goes on and on in the form of the teacher-disciple race from deities, to Siddhās, to sages, and to human beings. An important person in this race is Śree Bhāskararāya, who lived in 1690-1785 C.E. He is such a great man, that he has written many books like Varivasyā Rahasyam, Setubandham, Soubhāgya Bhāskaram (commentaries for Śree Lalita Sahasranāma hymn) and Drusabhāskaram. He followed the path of Vedas. However, he performed various sacrifices and worshipping of Śreedevee without fail and showed this path to his disciples. In the same manner, Avalānanda Nātha alias Arthor Avalon, a Westerner, has published a number of scholarly treatise and helped this world. Thus, this worship has spread throughout the country. In the last century a great person called Śree Chitānanda Nātha got initiated into this worship from Śree Guhānanda Nāthar in Allahabad (who has sacrificed everything including his dress) for many years, practiced it, got the experience, and initiated it to many of his disciples. Many of his disciples are spread across the country. He has translated lot of books, which are the roots for Śreevidyā in Tamil. They are Varivasya Rahasyam, Kāmakala Vilāsam, Shakti Mahimnā Storam, commentaries for Trishatee, Subramanya Tatva and Nityāhnikam.

A great work done by him is the worshipping procedure called Śreevidyā Saparyā Paddhati. This has been formulated in an excellent manner based on the treatise called Nityotsavam by Umānanda Natha, Varivasya Prakāsam and Rahasya Varivasyai by Śree Bhāskararāya, Parasurama Kalpasūtra and Paramānanda Tantra. There is no doubt that the worshipping method followed by all in India as well as abroad is this method only. He approached many learned people, compiled various matters and made clear very subtle nuances. He himself has given many discourses on this. In the same way, he advised my Guru (Atma Vidyā Bhooshanam Vidyāvāridhi Sāstraratnākaram) Brahmasree Injikollai Jagateeshwara Sastrigal to give discourse in Tamil on the books called Śree Lalita Sahasranama, Setubandam, Kāmakala Vilāsam and Varivasyā Rahasyam, and helped the then living disciples. These books are very difficult and can be understood only by those who have solid in-depth knowledge on 3 or 4 sāstras. Many books have subsequently been published on the methods of worship and Nityāhnikam. However, it is surprising that, there is no value addition by adding something new or making the method easier.

There are four important methods in this worship of Śreevidyā viz., Samayāchāra, Vāmāchāra, Dakshiņāchāra and Koulāchāra. Out of these Samayāchāra and Dakshiņāchāra are based on Veda path. Whatever be the method, everyone can get Śreedevee’s blessings, by following what was instructed by the teacher.

Eligible candidates for worshipping Śreedevee: Only men or couples are eligible to do many rites or rituals mentioned in Veda. Ladies have become ineligible to do them. According to the saying; Na Gāyatryā: Paro Mantra:, only males are eligible to chant the Gāyatreemantra itself and the same is the case with other mantras also. The only route to reach the Dharma for those not belonging to the three castes is to serve all others. Hence the route of action (karma mārga) has become unapproachable for many. On the contrary worshipping Śreevidyā has become a method that can be easily always followed by all. Śree Krishna said in Śreemad Bhagavad Geeta (9-32); Striyo Vashyā: Tat Soodrā: Tepi Yanti Parāmgatim. Accordingly this method can be followed by all. This method can be followed easily by children, youth, elderly people, those who are with family, widows or widowers.

Equanimity: Equanimity is the first prerequisite that is needed for the worshippers of Śreevidya. This advice is the best in Traipurasiddhāntam rules, even before initiating the mantras. One should have a feeling that the method followed by him in worshipping Śreedevee is the best. At the same time he should not denounce the other methods or deities. The living beings in the world follow the methods of their own liking, which in turn are the results of actions done in previous births and according to their mental maturity. However, everyone should one day or other come to worship Śreedevee. Hence it is a crime to denounce other worshippers.

In the same manner, all the 64 arts are games of Śreedevee only. All those arts are forms of Śreedevee only. (235th) Chatushshashţiyupacārādhyā and (236th) Chatushshashţikalāmayee are Her names. Hence the other arts like music, dance, drawing, etc., cannot be ridiculed. In addition to understanding devotion to teachers, the worshippers of Śreevidyā have to understand one other important matter – that is self realization. The author of the Sutra, Parasurama, has clearly mentioned this. Hence each one must do the hearing, chanting and meditation as much as possible. Lack of interest is not in order in the path of knowledge.

Śree Lalita Sahasranama is the one which has to be chanted by worshippers of Śreedevee. A number of commentaries/ translations have been written for this. Some of the important ones are;

Even out of these the first one is incomparable. We read lot of translations for this book. The important one among them is the Tamil meaning by Śree G.V.Ganesaiyer. In the same way, Śree S V Radhakrishna Sastry also has clearly translated in Tamil. Still, lots of aspects mentioned by Śree Bhāskararāya in Sanskrit in secret way, have not been elucidated. They are to be obtained through teachers or those learned in sāstras and great worshippers, who have experienced it. The 1000 names in this hymn are like 1000 mantras. A message, conveyed once, has not been repeated again or in any other name. Hence, Śree Bhāskararāya has clarified through Chalākshara Sūtra about the cryptic letters for these 1000 mantras. In the same way some of the inherent meanings also have not been cleared in the above mentioned books.

I did through discourses, by the blessings of teachers and Śreedevee, from 1982 onwards, every Sunday, in Śree Gnanabhāskara Society about various books on tantra, mantra, sāstra and commentaries on Vedas, followed by Soubhagya Bhaskaram of Śree Bhāskararāya in detail in Tamil. This book is mainly published by taking notes from those discourses. Hence the question, that why a new Tamil translation, when already done by Ganesaiyer and all, does not arise. In the same way, something more than what is mentioned in the commentary of Śree Bhāskrarāyahas been discussed in the discourse from the tantras, as mentioned in other books like Jayamangala, Arthur Avalon, and C. K. Jaisimha Rao, and from the commentaries of Vedas. It has to be noted that the authors have included some of them in this book.

The time spent in compiling this book by me and by the members of the society is worthwhile in our life. An important use is that we develop a focused mind on Śreedevee during those days. The mental resolve of Śree Chidānandanātha to propagate the plays (leelās) and greatness of Śreedevee to this world is also another reason for the same. I pray with prostration in the lotus feet of the teacher, that in the same way other books also should be published in Tamil. Let the blessings of mother of this universe (Jaganmātā) be showered on all.

Advaita Vedānta PracharamanSahitya, Meemāmsā, Nyāya, Vedānta SiromaniVidyāvāriti, Advaita Siddh Ranākara

Dr. Goda Venkateshvara Sastri M.Sc., Ph.D, CAIIB

A bird's eye view of the contents of the Devi Bhagavata.

The birth of Vasus, the story of Pandavas, the destruction of the Yadu race, the great snake-sacrifice of Janamejaya, the son of Vishnurata (Pareekshit) and the stoppage of the same by Asthika, form part of the second skanda.

The Mother as Bhuvaneshwari, the controller of all worlds, the eulogies of the Mother by Brahma, Vishnu and Parameswara, and Sri Devi’s upadesa to them are clearly enunciated in the third skanda.

The efficacy of Vagbhava Bija (Aym) is made clear by the story of Satyavrata. The story of Viswamitra and the greatness of Kama Bija (Klim) together with Ramcharita form part of the third skanda.

In the fourth skanda the stories of Krishna and other incarnations of Vishnu are given in detail with the worship of Sri Mata. The fifth skanda deals with the slaying of Rakta Bija, Mahishasura, Bashkala, Durmukha, Asiloma, Sumba, Nisumba, Dhoomralochana, Chanda and Munda. The anugraha of Mother to the King Surata and Samadhi, forms the essence of the fifth skanda.

The sixth and seventh skandas deal with the story of Nahusha, Hyhaya, Ekavali, Thrisanku and Harishchandra. Mother acting as Maha Kali, Maha Lakshmi and Maha Saraswati and the different acts of their valor are explained with the help of many stories. The swift and brave Maha Kali, the joy and intoxicating sweetness of the Divine in the form of Maha Lakshmi, the knowledge, harmony and calmness personified as Maha Saraswati and many verses in their praise are found as we go till the end of the tenth skanda.

In the 11th skanda the modus operandi of the upasana, various ‘dos’ and ‘donts’, the efficacy of rudraksha, vibhuti, sandhya, pooja and other rituals including Ramya and prayaschitha (expiatory) rituals are codified.

Devi Kavacha, Gayatri Kavacha and Gayatri Sahasranama, the story of Kenopanishad and Chintamanigruha are beautifully depicted in the last portions of the purana.

A study of the Devi Bhagavata Purana will open new vistas of knowledge and certainly generate devotion to the feet of the Divine Mother ultimately leading the individual soul to liberation, after the enjoyment of all worldly objects. Thus, sage Veda Vyasa in his infinite campassion and limitless devotion to the Holy Mother gave us the Srimad Devi Bhagavata, the essence of the Vedas. The conception of God as Divine Mother dates back to the time of Vedas, references of which could be seen in Rig Veda and Chandogya Upanishad. Among the many conceptions of God, the form of Sri Mata got the attention of many great souls as being identical with Supreme Brahman. She is the indweller of all creations, controlling man’s activities from within. In her compassion she takes different forms as Kali, Thara, Lakshmi and Saraswati for the benefit of devotees of different orders. They are all her different Vibhutis, or manifestations.

In her Para form she is immutable, eternal and beyond the limitations of time and space. But an ordinary human mind which thinks of only limited objects with name and form will not be in a position to comprehend Her para form. It is to cater to the needs of such mandaadhikaris the Supreme takes myriad names and forms with her ananta sakti. But still she is immutable. Her presence could be experienced by a Jnani in the roar of a lion, in the song of a bird and in the cry of a baby.

Sage Veda Vyasa, the unlimited ocean of knowledge who had codified the Vedas, compiled the Brahma Sutras, and commented upon the Yoga Sutras of Bhagavan Patanjali, had also taken up the task of writing the puranas for the common man. Puranas fall into two main categories, namely, Maha puranas and Upa-puranas, each 18 in number. Srimad Devi Bhagavata is a Maha Purana glorifying the Mother as Supreme. In Srimad Devi Bhagavata there are 12 chapters and 318 sub-sections, called adyayas, with 18,000 slokas mostly in anushtup metre. Devi has been portrayed as the creatrix of all the worlds, the sustainer and destroyer of the same. She is thus the material as well as ostensible cause of the whole world. All the worlds appear on the screen of the mother only to fade away and become identical with this screen. She is both transcendental and worldly.

In the first skanda, Devi has been protrayed as all-powerful and supreme. The birth of Suka and the killing of Madhu and Kitabha have been explained in detail.

The teaching of this purana to Sage Suka and Suka’s meeting with King Janaka at Mythila are some of the peculiar stories one finds in Devi Bhagavata. The marriage of Suka with Peevari and the birth of four sons, Krishna, Gowraprabha, Bhuri, Devasrutha and a daughter called Keerthi are explained in the 19th chapter in the first skanda.

Keerthi was given to Anuha in marriage, and they begot Brahmadatta as son. Brahmadatta was initiated in Devi Upasana by Sage Narada. By upasana of the Maya Bija, Brahmadatta got Jnana which ultimately led to his liberation from samsara.

Dr. Goda Venkateswara Sastri

MĪMĀMSA NYAYAS IN MODERN LIFE

Mīmāmsā stands for that branch of learning which is concerned with the interpretation of the Vedas. This system was originally created to explain the application of the Vedic mantras in the rituals generally called yajña. Hence it is ritualistic in nature and deals with the karmakāņda section of the Vedas. In the modern days, yajñas have become rare and Hindu religion has been reduced to going to temples and doing idol worship. On the other hand, ancient Hindu religion consisted of performing various rituals in the sacrificial fire. Their gods were Indra, Agni, Sun, Vayu etc. Although yajñas are not popular now, the rules of interpretation of the Vedas are ever relevant. These rules have percolated into the society in all its branches and are being applied by all without recognizing that they owe their origin to Mīmāmsā.

Vedas consist of two major portions namely the Mantra or Samhitā portions and the Brahmaņa portions. The Brahmaņa portions depict various rules for performing the yajñas. As days passed on and with the changes in the language and the passage of time, these portions had become incomprehensible. Thus, a need was felt for the creation of the rules of interpretation. One more reason is that the texts of various Brāhmaņas were generally unsystematic, incoherent with many ambiguities, apparent inconsistencies, conflicts, vagueness etc. Maharşi Jaimini had taken up the task of systematic interpretation of the Mīmāmsā rules. There were many seers who tried earlier to interpret the same; but in Jaimini we find a perfect and complete set of rules of interpretation. Jaimini himself had referred to eight earlier writers in his sūtras. These are in twelve chapters starting from the definition and proof for the Dharma. Many commentaries were written to explain the Jaimini sütras as they were terse and concise. Today we have only the commentary of Sabarasvāmin, which too was further commented by many luminaries like the great Kumārila Bhatta, Prabhākara Miśra, and Śālikā Nātha. Apart from these commentaries and their super-commentaries, many ācāryas like Äpadeva, Laugākși Bhāskara, Śankara Bhațța wrote standard works to explain various rules of interpretation in a simple and lucid way.

As seen above, the rules of interpretation of Mimämsä were created for the correct performance of Vedic rituals namely yajñas etc. However, since these principles were extremely rational and logical, they began to be subsequently used in other branches of universal application. Sańkarācārya has used the Mimāmsă Adhikaraņas in his commentary on the Vedanta sūtras”¹.

Before going to the rules of interpretation, it will be useful to understand the structure of the Vedas and the Brahmaņas in particular. The Samhitā portions of the Vedas are full of mantras containing the praises of various deities. These non-obligatory statements are termed as arthavādas. These do not lay down any injunction. However, they should not be taken as useless. An arthavāda is a statement of praise or explanation akin to the preamble or statement of objects in a statute. Though it may not have a legal force by itself, it can help to clarify an ambiguous text or give the reason for the same. The Brahmaņa portions contain obligatory rules called as vidhis and nisedhas (vidhis in a negative form). They are generally classified as four kinds as below:

Nişedhas too are vidhis but in a negative form like ‘do not speak lie’, ‘do not harm any being’, ‘do not kill a Brahmin’ etc. There are other quasi-vidhis termed as niyamas and parisankhyās apart from the above vidhis.

These Vedic sentences need interpretation since there are apparent contradictions in more than one place. Generally, the axioms of interpretation are as under:

Every effort was made by them to reconcile contradictions. They also held that a vikalpa has to be resorted to only in such cases where all other means of reconciliation failed since vikalpa will attract eight faults.

There are six general principles by which an applicatory injunction (viniyoga vidhis) is used to indicate the connection between a subsidiary action and the main action. They are called śruti, linga, vākya, prakarana, sthāna and samākhyā. A brief account of these is given below:

Apart from these, there are some other principles that are constantly used in Mīmāmsä which are of much use in our day-to-day life and in legal contexts. Some of them are given below :

1. The principle of Atideśa: There are two different kinds of yāgas given in the Vedas. One is called the primary yāga (prakṛti yāga). All things necessary for the performance of the yāga are given while mentioning the yaga. But when certain yāgas which differ from this prakṛti yāga, only in minor details are stated, then only those portions where there are variations will be mentioned. Rest of the actions has to be followed as explained in the prakṛti yaga. These subsidiary yāgas are called vikṛti yāgas. Darśa-pūrņamāsa is a prakṛti yāga. The rules of performance of the same are given in the first chapter of the Satapatha Brāhmaņa.

Another prakrti yaga is ‘Agnihotra’ and rules of the performance are given in the second chapter of the Brahmana. Saurya yāga is a vikrti yāga. Rules of performance for the same are not given. Sruti says that it must be performed as per the rules given in its prakṛti yāga namely Darśa-pürņamāsa. Thus we understand that a vikṛti yāga has to be performed as per the same rules of prakrti yaga of the same category. This principle of ‘prakṛtivad vikṛtiḥ kartavya (performing as per the rules given in its prakṛti yāga) is known as atideśa. This refers to the principle of going from known to unknown. If this principle is not accepted, then the Vedas will have to give minute details of each yāga. These yāgas are infinite as the desires for fulfilling which these yāgas are given are also infinite. Then naturally the Vedas will become very voluminous, and it may not be possible to retain them in memory.

This atideśa principle though created for religious purpose found its use in the field of law also. For example, the adopted son was considered to be legally on the same footing as that of a regular son. A male child born to a person through his legally wedded wife is called an ‘aurasa putra’ or biological son. When a couple is childless, law permits them to adopt a son. Such a son is called an ‘adopted son’ or dattaka putra. Smrti texts are silent about the rights and duties of such a dattaka putra. By applying this atideśa principle, dattaka putra or adopted son is considered on the same footing of an aurasa putra with the same rights and duties. Here the regular son is treated as prakṛti yāga and the adopted son as a vikṛti yāga.

This nyaya can be applied in solving the problems related to administration, like the case Sardar Mohd. Ansar Khan vs State of UP 8. In an intermediate college in Uttar Pradesh two persons were appointed as clerks on the same day. Both were equal in their qualifications and service record. When a post of head clerk became vacant, a question was raised as to who should be promoted. The rules and regulations in the Education Act of UP were silent on this point. But there were regulations regarding the promotion of teachers to a higher post which state that if two teachers are appointed on the same day then the senior in age will be eligible for promotion. The rule applicable to teachers was applied for non-teaching staff also and judgement was given. It can be seen that the principle of atideśa is applied in the instance cited above.

2. The principle of Abhidhā: Abhidhā stands for literal rule of interpretation. There is no option to relax the rule; but one has to follow the rules strictly as given in the Śruti texts. Only then will a person get the result. As the result is not seen by the doer in his life time, he has no chance to verify. In such cases one has to strictly follow the injunctions as given in Vedas for getting the results. This is applicable to the case of the will written and registered by a person. After his lifetime, the terms contained in the will have to be strictly followed. There is no possibility to change, unless some of the clauses are vague or not clear.

3. The principle of Lakşaņa: This is against the abhidhā principle. Here the intention of the person is taken into account rather than the text itself. Let us take a text as ‘kākebhyo dadhi rakṣatām’ ‘protect the curd from the crows’. Here the word ‘kākebhyo’ is only illustrative and does not mean only the crows but all the birds/animals. Thus a boy who was given this command cannot simply be watching when a cat, dog, or some human being comes and eats the curd. He cannot say that he was asked to protect the curd only from the crows and will not interfere when any other thing comes and consumes the curd. The intention of the person who gave the instruction ‘protect from crows’ is to ‘protect from all things that may eat the curd’. Thus the word ‘crow’ here has to be taken in an extended sense or by the principle of laksana to mean, ‘all objects that may destroy the curd’.

This principle has been used in courts of law also. In the Udai 10 Sankar Singh vs Branch Manager Case, the petitioner was riding a scooter and a truck hit him. In the accident, one of his legs was hurt and later it was amputated. Because of the shock or otherwise, his hand was also paralyzed. He was holding a policy with the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) and he claimed compensation from them. The rules of LIC said that a policy-holder was eligible for compensation only on death or permanent disability. Permanent disability was defined as (i) loss of both the eyes; or (ii) amputation of both the legs; or (iii) amputation of both the hands; or (iv) amputation of one hand and one leg. LIC rejected the claim following the abhidha principle or literal rule of interpretation. Courts, however, allowed the petition, taking into consideration the principle of lakşaņā. Here the intention of the framers of the rules has to be taken into account. Paralysis of hand is as bad as amputation of the hand, because in both the cases one can have no use with the hand. The word ‘amputation’ is only illustrative in this context and not exhaustive. LIC was asked to pay the compensation for the loss of the hand. Thus we find the use of this principle in legal circles too.

4. The principle of substitution- Pratinidhi nyaya: This principle states that for a compulsory action when the substance ordained is not available, one has to do the same with a substitute which is very near to it. Thus in Somayāga when it is not possible to get soma creeper in the surroundings, then the sacrifice may not be performed because of the difficulty of getting the requisite material. But the Vedas say that in such a case, one may perform the yaga with ‘pūtika’, a creeper similar to the soma creeper. One should not stop from doing the compulsory rite because of the non-availability of the said material but perform the same with a substitute. This is similar to our taking wheat when rice is not available.

This principle also found its use in legal cases. A certain person was arrested under the TADA Act (Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Act). The Act provides for applying for a bail by a person arrested under the above Act to the designated Judge. The designated judge was the District Judge. A difficulty arose as the High Court did not make selections and a District Judge was not posted for that district. The concerned person was languishing in jail for more than eight months since no authority for applying bail was available. The case went to the higher court where it was decided that under the rule of substitution the senior-most Additional District Judge could grant bail since he was nearest to the District Judge.

5. Kāmsya bhoji nyaya: This nyāya is stated in the twelfth chapter (sūtra 2) of Jaimini sūtras. According to this, there is a vrata for a disciple to take food in a vessel made of bell-metal only. Also there is a condition that he should take food only in the plate in which his teacher has taken food. Now even though the teacher has a silver plate in which he can eat his food, still the teacher chooses to take food in a plate made of bell-metal only so that the vrata of his disciple will be fulfilled..

We find this principle in vogue even today. In certain institutions, there are uniforms fixed for all the employees. Also in the same institution there was an understanding that the master will not wear garments that are costlier than those worn by the employees. Now the master even though he can afford costly clothes, will not wear them at office since that will be against the accepted conditions. These practices are seen in many organizations even today.

6. Dehali dīpa nyaya: Though this nyāya is not explicitly stated in Jaimini sütras it is used in Mīmāmsä works many a time. It means that a light kept at a door-step will light all the objects inside and also outside the house. This is explained by the joint account of the couple in a bank. Even though the account is one, it helps both the husband and wife to deposit or withdraw money independently.

7. Brahmaņa parivrājaka nyāya: This nyāya is stated in the Tantra Värttika. This states that special preference has to be given to one over equals. Here parivrājaka means a person who has taken up sannyāsa. There is an opinion that only Brahmins are eligible for taking up sannyāsa. Thus a parivrajaka also is Brāhmaņa but who has taken sannyāsa. When some benefit is extended to Brahmins, it automatically applies to sannyāsins too since they too are Brahmins. But it is extended to them first since they are not only Brahmins but also sannyāsis. This special treatment is referred to by the above nyāya.

8. Upakramādhikarana nyaya: This nyaya states that a word known first with a certain connotation should be taken in the same meaning even when a later part of the sentence containing the same word gives some other meaning. This is akin to the worldly usage that the first impression is always to be taken.

9. Apacchedadhikarana: This nyaya is stated in the context of soma sacrifice. Various priests in the yaga move from one place to another holding the garment of the preceding priest. When a priest releases the hold of the garment of the earlier priest, a parihara (corrective action) is given and later if some other priest releases the hold of the garment, another corrective action is given; these contradict with each other. In a particular context when both the priests release the garments, the question arose as to which parihara should be taken up. It was decided that the latter one stands and has the effect of cancelling the earlier one. This is what we follow in our offices when we say the latest set of rules supersede all earlier instructions.

There are many more nyāyas in Mīmāmsā-śāstra which when we closely study, are useful to our day to day life. This śāstra needs to be well read and various nyāyas given in it have to be utilized for the welfare of the society.

GODA VENKATESWARA SASTRY

FALSITY OF THE WORLD

The main tenets of Advaita can be known from the simple sentence “Brahma satyam jagan mithyā jīvo Brahmaiva naparah”. That is to say, (i) Brahman alone is real, (ii) the world is false and (iii) the jīva is none other than Brahman. Thus barring Consciousness either in the form of Brahman or Jiva, the rest of the world is false according to Advaita. Hence the Advaitins are called illusionists. On the other hand, the Dvaitins view the world as real. For them the world is as real as its cause. They are, therefore, called realists. The fight for establishing one’s system by refuting the tenets of the opponents had a long origin. Bādarāyaņa in his Vedānta-sūtra refutes many arguments of the Dvaitins (those who advocate the theory of many souls). Šankara too in his Sūtra-bhāşya had severely dealt with the Naiyyāyikas, Sankhyas and other dualists. The commentators of Sankara like Padmapāda, Sureśvara, Vācaspati Miśra and Vimuktātman followed suit and refuted Dvaita to establish the Advaitic viewpoint

But the real controversy between the Advaitins and the Dvaitins started with the work Nyayamṛta of Vyasatirtha. Vyāsatīrtha has actually formulated the refutations of Advaita, which were given as pūrvapaksas found in the Advaita texts starting from the Brahmasiddhi of Mandana up to his time. But he did not state from where he laid his hand to those refutations. But this work has pushed Advaitins at that time to a corner. Many Advaitic ācāryas took up cudgels against Vyāsatirtha and refuted the arguments given in the Nyâyâmṛta. The Bhedadhikkara and the Advaitadīpikā of Nśsimhârama are some of the works that refuted the Dvaita views before establishing Advaitic standpoint. The Madhva- tantra-mukha-mardana of Appayya Dîkşita also has to be taken into account for its frontal attack on the Dvaitins. But refutation verbatim-et-litleratim to the arguments contained in the Nyâyâmṛta was not taken up by any one till Madhusūdana’s Advaita-siddhi. The advent of Advaita-siddhi inaugurated the birth of a series of polemical literature. Many terse philosophical texts came up in the form of refutation of each one in both the schools. One thing may be noted here that the navya-nyaya method of dialectical arguments was employed. This attracted the attention of all learned scholars, who started reading the original works and their commentaries along with the refutations, replies, counter-refutations, etc. The series of works from the Nyâyâmṛta could be codified as under:

Nyâyâmṛta

by Vyasatirtha

Advaita-siddhi

by Madhusūdana Sarasvati

Tarangini

by Rämatirtha

Siddhi-vyākhyā

by Balabhadra, refutation of Tarangini

Nyâyâmṛta- kanțakoddhāra

by Vijayendra-tirtha Anandabhattāraka, refutation of Siddhi vyākhyā

Guru-candrikä and Laghu-candrikā

by Brahmananda Sarasvati refutation of Tarangini

Tarangini Saurabhā and Nyāyāmṛta Saugandhya

by Vanamālimiśra

Vittaladeśiyi.

by Vittaladeśiya-upadhyaya- refutation of works of Vanamālimiśra

Nyāyāmṛta Saugandhya Vimarśa

by N.S.Anantha Krishna Sastri

The keynotes of the rival schools of Advaita and Dvaita centre round two slogans generally quoted are:

Brahmaivedam Jagat sarvam brahmanonyan na vidyate

Brahmanonyad bhäticen mithyā yathā maru maricikā.

The Dvaitins, however, maintain that

Yādṛśam brahmanah sattvam tādṛśam syājjagatyapi

Tattrasyāt tadanirvācyam chedihāpi tathāstunah.

Both of them produces ruti texts in support of their views. The sūtras of Badarâyaņa also were interpreted to suit their preconceived ideas. Arguments and counter- arguments over the past four centuries did not alter the position of both the sides. Both of them stuck to their views with unshaken faith in them and were convinced with their position. Hence arguments, refutations and sometimes accusations, etc. did not alter their positions. Perhaps, the only benefit that accrued as a result of this polemics is the considerable growth of dialectics in Indian philosophy. A brief analysis of the five definitions of falsity (mithyatva) is taken up for study in this article.

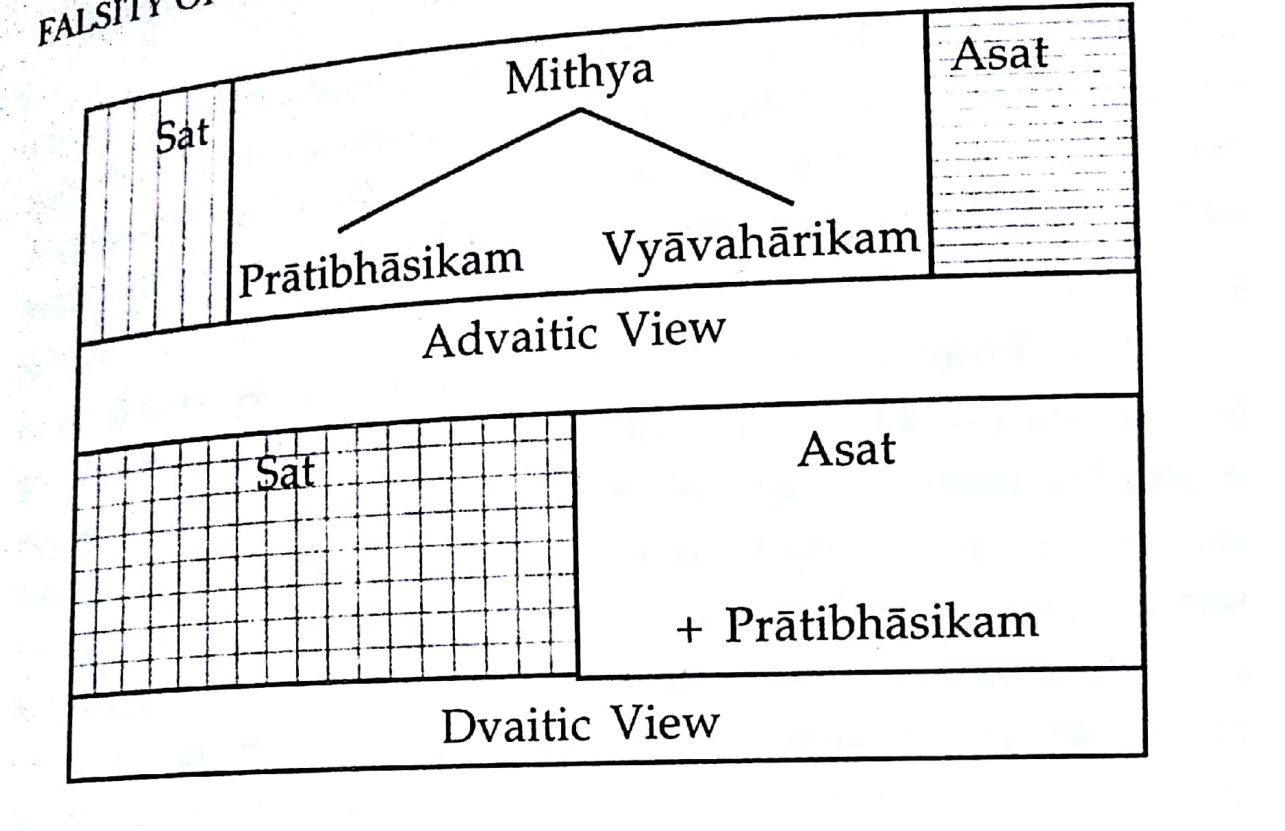

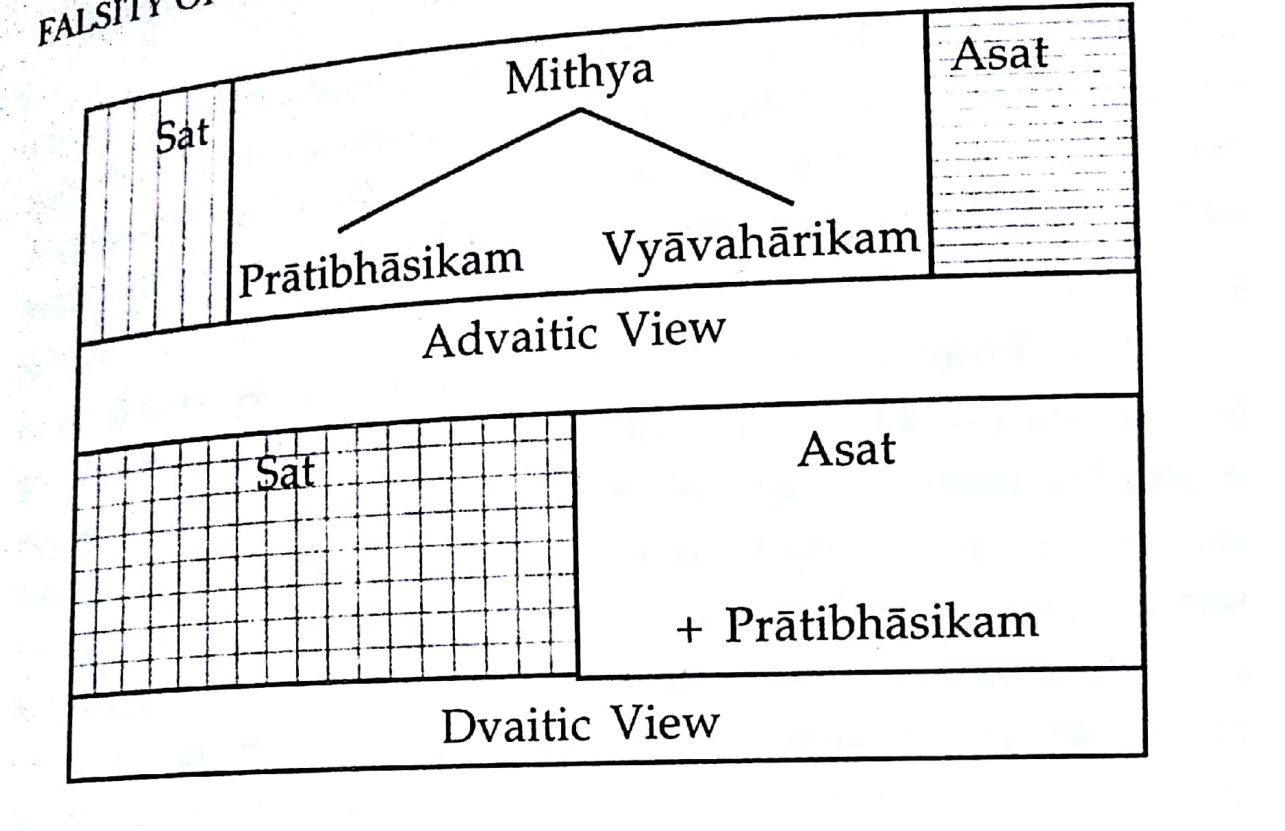

The Advaitins had to resort to the falsity of the world to establish the oneness of Brahman without a second. If the world has the same ontological status as that of Brahman, then the advitīyatva (being one only without a second) will be at stake. Hence Brahman has been afforded the status of transcendental nature. It is transcendental, because it does not cease to exist in all the three periods of time. The world, however, being a product of māyā, will continue to exist till such time the Brahman-knowledge dawns on the individual. When Brahman is realized, automatically the nescience or mâyâ is annihilated. The individual is released from all the bonds. Hence the world cannot have the same transcendental status as that of Brahman. There are other objects like the silver seen in a shell, snake comprehended falsely in a rope, which are falsified even before the Brahman-knowledge dawns. In fact, they are annulled by the knowledge of their substratum. Such objects have an ontological status called pratibhāsika (phenomenal existence). Apart from these three kinds of things, there are, however, some more objects which are dealt with during discussion in Advaita. Consider, for example, objects like the horn of a hare, son of a barren woman, milk of a tortoise, sky-flower, etc. They do not have any ontological status as they are not comprehended at all. They are figments of our imagination. It is the power of our minds which is responsible for the same. The Dvaitins, on the other hand, are pluralists. They hold that the world has the same reality as that of its cause; hence it is as real as Brahman. Objects of phenomenal reality are included in the last category, namely, tuccha or asat, like the son of a barren woman. (pl.see the diagram).

According to the Advaitin, Brahman knowledge alone is the panacea for all the ills of transmigration.¹

Only when Brahman is experienced directly, mâyâ and its effects including various limitations will cease to operate. Also, all the karmas, save the one which is responsible for the present birth, which he had carefully saved all along will be burnt by the Brahman knowledge. The karmas that started this birth has to be exhausted through experience. Finally, when the body of the jñāni falls, there is no balance of karma, and so he becomes free from birth. The dawn of the Brahman-knowledge will occur only when one has the firm knowledge of the non-dual Brahman obtained through hearing the same from a qualified Guru, by reflection and by meditation. This firm conviction of Brahman will come after the advent of the knowledge of the falsity of the world, the reason being that, if the world is also true how can Brahman be one only without a second? Hence ‘the proof of the truth of non-duality follows from the proof of the unreality of all duality or plurality. Hence at the very outset, it becomes necessary to prove this unreality. To this end, five definitions of unreality given by the earlier ācāryas were taken up for establishing the false nature of the world by refuting the adverse arguments advocated in the Nyâyâmṛta. These definitions of falsity are given below.

1. From the figure shown above, an object which is in the central set will be different from Sat and asat. Thus it can be said that any object in the set of mithyā has the absence of sattva and also the absence of asattva, either individually or collectively. Thus the definition of mithyātva is formulated as: possessing the combined or separate attributes of the absolute negation (atyanta abhāva) of non- being (asattva) as accompanied by the absolute negation of being (Sattva). This definition follows the statement of Padmapāda, a senior disciple of Sankara in his ‘Pañcapâdikâ as “the word unreal denotes undefinability, (anirvacanīyatā)”, it might be held that what is meant by the ‘unreality’ of a thing is that it is undefinable, i.e. that it is not the substratum of either being or non-being.

2. It is the correlative (pratiyogin) of absolute negation (atyantābhāva) with regard to the substratum in which it is cognized. When a jar is called as unreal, we mean that it is capable of being absolutely denied in regard to the point of space and time in connection with which it is perceived. This comes from the śruti text ‘Neha nânâsti kiñcana’.5 This falsity is taken from the book “Pañcapâdikâ vivarana’ of Prakāśātman.

3. Unreality is the character of being set aside or discarded by cognition (true knowledge of the substratum). This is also taken from the ‘Paņapâdikâ vivarařa’ of Prakśātman. It is based on the Sruti text “Vidvān nāma rupāt vimuktah

4. Unreality is the character of being cognized in its locus where there is the absolute negation too. It is based on the Śruti text “Na tatra ratha na rathayogā na panthānah atha rathan rathayogan patha sṛjate.”” It is taken from Citsukha’s work by name Pratyak-tattva pradīpikā.

5. Unreality of an object is its being something distinct from existence. This is from the Nyaya-makaranda of Ānandabodha. It is based on the Śruti text “Atonyadārtam.”8 Though five definitions are mentioned, on scrutiny there are only three distinct definitions. The fourth definition is nothing but a recast of the second definition as there is an interchange of substantive and attribute only. Similarly, the fifth definition is nothing but the first definition as it is necessary to incorporate distinction from non-existence also in the definition. Otherwise, the definition will be too wide on ‘son of a barren woman’, etc. We thus have only three separate definitions left over for detailed study.

First definition of falsity.

This is the earliest definition of mithyātva (falsity) given by Padmapāda. Its form is Sattva atyantābhāva, asattva atyantabhava dharmadvayam or Sattva atyantābhāvavatve sati, asattva atyantābhāva rupam viśistam.

Before understanding the above, we will have to understand certain terms of the Sastra. Here sattva means trikāla abādhyatva-that which is not sublated in all the three periods of time; in other words, existing in all three periods of time. Only Brahman belongs to this set. Śrutis clearly state this position as “anuchitti dharma,” “atonyadārtam.”10 The other extreme to this is asat- that which never exists. The examples to this are ‘horn of a hare’, ‘horn of a man’, ‘son of a barren woman’, ‘milk of a tortoise’, ‘flower of skies’ and so on. These are never comprehended as ‘existing’ with reference to any place or any time. Can anybody say that he had comprehended the son of barren woman at any period of time anywhere? Or will it be possible to do so now or at any later period? Such objects are called tuccha. Even the Mahabhāṣya the earliest written text now available, explains this concept. The third set is the set of mithyā or illusory objects to which the world belongs. The objects in the world are perceived by us through our sense organs. But they are not ever-existent. Some objects may have a long span of existence like space, air and so on; whereas some other objects are impermanent. They fade away before our own eyes. They cannot be categorized as Sat as they are not ever-existent like Brahman. As they are comprehended by us through our sense-organs either directly or by other means of valid knowledge like inference and so on, they cannot be categorized as asat. Hence is the necessity of the third category, mithyā. The objects seen in a dream too belong to this category. They are comprehended as though existing at that period of time. But their existence is sublated by the jāgrat (waking experience). The experience of the common man is that the objects comprehended in a dream are illusory. In the same way, all the objects seen in the waking state are also illusory since the Vedas proclaim that, by the knowledge of Brahman, the existence of duality (dvaita) will be sublated. “jâte dvaitam na vidyate.”11

The Dvaitins do not agree to this categorization of objects. According to them, there are only two sets of objects namely Sat and asat. This is totally against the Vedic teaching and the common experience as stated earlier. The Vedas say that Brahman had become Satyam, Anṛtam and Asatyam, 12clearly enunciating the three states of epistemological existence. The non-existent asat cannot be included either in Vyavahārika (empirical) or in prâtibhâsika (illusory) state. This is the main reason of misunderstanding of advaitic position by the dvaitin.

Thus by definition, Sat, asat and mithya each being distinct by itself; the absence of both Satva and Asatva can exist simultaneously in a mithya object.

The Tarangini criticizes Advaita on the ground that the statement “asat cet na pratīyeta” (if it is asat, then it may not appear) does not make any sense since the prayojaka and prayojya are identical in the argument. This criticism is due to non-comprehension of the Advaitic position. Let us analyze the same:

If we take a pot for our discussion, the pot does not clearly belong to the first category Sat as it ceases to exist when it is broken. It may exist for a thousand years. But there is no guarantee that it will continue to exist. The fall of a single block of wood is enough to break the pot and cease its existence. Let us examine whether it is an asat. Clearly it (the pot) does not belong to asat as one can see the pot, touch the pot and pour water in it and use it as he likes. Such actions are not possible with an asat object like the ‘son of a barren woman’, or ‘horn of a hare’. Now the pot by the above argument clearly does not belong either to Sat or to asat. But it exists as it is the object of our perception. Hence it belongs to the third category called mithyä. There is no special significance of naming the category as mithyā except that any object can be either (i) Sat or (ii) asat. An object, however, cannot be simultaneously belong to both, that is (iii) Sat and asat as they are mutually exclusive, one ever-existing and the other never-existing. Hence the fourth possibility is inexplainable that is mithyā-not belonging to either of the categories. This set is experienced by everybody in the world irrespective of his status whether he has read the śāstrās or not. Such a common experience cannot be repudiated by any one. (see figure).

Now the Dvaitin analyses the definition of mithyatva and says whether it is

1. Absense of Sat qualified by asat; (asattva viśişta sattva- abhava)

2. Absence of Sat and absence of asat (sattva atyantabhava vatve sati asattva atyantābhāva) or

3. Absence of Sat qualified by the absence of asat. (sattva atyantābhāva viśişța asatva atynatābhāvah)

The first explanation fails at the first stage itself as the Advaitin never agreed nor stated anywhere such a position.

For the second explanation, the Dvaitin adduces three flaws. The first is (i) contradiction as, if there is no Sat it should be asat and vice versa.

Apparently this is due to non-comprehension of Advaitic position that there are three categories namely Sat, asat and mithyä. If the world does not belong to Sat it may either belong to asat or mithyā. Similarly if the world does not fit in asat it may belong to either Sat or mithyā. Clearly in this case, as it is stated that the world does not belong to either Sat (the first category) or asat (the second category), naturally it belongs to the middle category namely the mithyā. Hence the criticism does not hold water.

The next criticism is the world may be of the form of Sattva like Brahman which does not contain Sat but in the form of Sat. (like sugar which does not contain sweetness, but is sweet).

The answer of the Advaitin for this is that it is not necessary to accept another sattva in the world separately. Brahman is Sat and the world appears to be Sat as it is superimposed in it. Hence to accept Satva apart from the Brahman-Sat is redundant. Also by accepting it, all objects in the world appear as Sat uniformly. If, on the other hand,a separate Sat in the world is accepted, then different objects will be connected to Sat differently as in the Nyaya School.

The third flaw is that the mithyatva is not available in the example śukti-rūpya (silver appearing on the shell). The reason is in śukti-rūpya, absence of sattva exists since it is different from Brahman, the Sat. Hence it cannot hold the Asatva-abhava (absence of asat). The answer to this is that Sat and asat are not mutually exclusive. Even when Sat does not exist in śukti-rūpya, it need not be asat also according to the definitions of Sat and asat given above. Hence all the three flaws of the Dvaitin do not affect the advaitic position.

The third explanation of this definition was scrutinized and the same three fallacies were made by the Dvaitin. Thus by the explanation given above, these three fallacies also do not affect the Advaitic standpoint.

As the absence of gotva (cow-ness) and aśvatva (horse- ness) can co-exist in gaja (elephant), the absence of Sattva and asattva can co-exist in an illusory object. There is thus no contradiction in this definition of mithyātva. Also, this explanation is not the brain child of Advaitin, but given in śrutis, smrtis and Purâņas. Non-acceptance or rebuttal of the same only proves the ignorance of the above texts by the Dvaitins.

Also for the objection of the Dvaitin that the absence or difference of asat is already known to be present in the world and hence proving the same by the anumâna (inference) is redundant; the answer of Advaitin is that we prove not only absence/difference of asat but also the absence/difference of Sat also in the worlds. Hence it is not redundant. Also such a position is accepted in the pantheon of Sâtras as such usages are found in the criticisms and answers between the Mīmâmsakas and the Logicians.

Also it should be noted that Brahman is free from Sattva and asattva. It transcends both. It is, however, Sat in its form like sweetness in Sugar. Hence objections of the Dvaitins pale away in thin air and the definition of mithyatva given by Sri Padmapâdâcârya is perfect.

Second definition of falsity.

Prakāśātman wrote a commentary on the Pañcapâdika of Padmapāda in which he has given two definitions for the falsity of the world. This is the first one. It is thus: Falsity is the co-relative of negation at all the three points of time in the very same locus where it appears. 13 Silver appearing in a shell is the example given in this case also. As silver does not exist in all the periods of time in the shell where it appears, it becomes co-relative of negation ‘silver is absent in this (shell)’.

The author of Nyāyāmṛta discards this definition. He asks: what is the ontological status of the co-relative of the eternal negation in the locus where it appears? Is it

(i) real; or

(ii) apparent; or

(iii) empirical?

In the first case, the thesis of non-dualism gets affected as there are two real objects, Brahman and the said co- relative. In the second case, the argument of Advaitin involves the fallacy of establishing what has already been established. In the last case three defects arise. They are’

(i) Being empirical it will negated at a later time and thus it will not be contradicting absolute Brahman. Thus there is a fallacy of proving an unintended thesis (artāntara);

(ii) It implies that the advaitic texts are not expressive of ultimate truth; and finally

(iii) It establishes the absolute reality of the world; since it is not apparent it must be real.

Madhusūdana Sarasvati’s replies to these are as under:

All the above charges are not justified. There are no proper grounds for raising the same. Even if the co-relative of the eternal negation is to be real, the thesis of non-dualism is not affected since the negation of the world is identical with the Brahman which is the substratum or locus of the negation.

Nor can it be objected that the negation being real, the co-relative of the negation namely, the world is also real. The rule that the negation and the co-relative should be of the same order of reality cannot be accepted since there is an exception in the case of silver in the shell; as the negation of silver in the shell is real whereas the shell-silver is illusory.

The second option is not accepted by the advaitins and hence to object that is wrong. The third option namely that the negation is empirical is being answered thus.

(i) It cannot be said that the negation too being negated at a later time, it will not be presenting the absolute reality of the worlds leading to the fallacy of arthantara (proving unintended thesis), as we find that when the dream is negated the objects seen in the dream are also negated. The reason of the negation being non-contradictory to the reality is not due to negation of negation. It is because that the negation is of lesser status (of truth) than that is negated. In the present case the negation and the negated are both of the same status. Hence they are opposed to each other.

Nor it can be said that when the negation is negated, the co-relative regains reality. It is only at those places that by negating the negation, the co-relative will regain greater reality, where the act of negating the negation is done with an intention to re-establish the reality of the original object in question. In other words the negation of negation alone is the intention and not to negate the counter-position also. This is better understood by the example where a person gets a false knowledge in silver as ‘This is not silver’. Then it is negated as ‘this is not non-silver’. This negation will re-establish the reality of the silver. Where the intention is to negate the earlier negation as well as its co-relative, then the negation of negation will not establish the reality of the co-relative. This is like negating the pot and its absolute negation at the time of destruction of pot in the parts of the pot. Now the negation of absolute negation of pot does not posit the pot.

Similarly, in the present case the world and its negation, both are negated by the same argument, knowability (dṛśyatva). Hence even if the negation is negated, the world does not regain greater reality, since the determinant of the negation is common to both.

Objection of the Dvaitin: Since the negation of the world given by the śruti is not real, rutis concerned may be invalid.

Reply: No. As the śrutis reveal the not real as not real, it is not possible to reject the validity of the śrutis.

Objection of the Dvaitin: Is the negation of this negation determined by its intrinsic nature? (svarūpeņa nişeda) or is it regarded as determined by the character of being ultimately real leaving its (of the world) nature distinct from the unreal?

The first alternative is not true as it is wrong to negate the world that exists at the time of appearance distinct from the unreal object as not existing in all the three periods of time. This is because the śruti explains that these objects in the world

- have origination;

- have causal efficiency;

- have nescience as their material cause; and

- are destroyed by the knowledge of reality. Thus they are distinct from unreal objects. They are related to the time of their appearance. They, therefore, cannot be negated intrinsically in all the three periods of time in the locus of their appearance.

The second alternative is not possible. This is because the reality is uncancellable. Uncancellability is to be understood as the negation of cancellability. Hence the fallacy of mutual dependence will arise. (The concept of falsity involves the concept of reality and the concept of reality involves the concept of falsity. Thus each has to be understood as the difference of the other only).

Also if the character of being real is negated intrinsically (svarūpeņa), then all the fallacies of the first alternative too will result. If it is said that the character of being real is also negated as being determined by the character of being real, then infinite regress will result.

The Advaitin answers that both the world and the silver on the shell are eternally negated as being determined by their intrinsic nature. This concurs with our experience that after the cognition of the substratum (the shell), the silver in the shell is negated as ‘there is no silver now nor was there silver before, nor there will be silver even at a future time’. This negation is in the form of its intrinsic nature (svarūpeņa nişeda). Similarly the negation of the world by the Sruti ‘Neti, neti’14 is also a negation in its intrinsic nature.

Objection by the Dvaitin: The co-relative of the negation is only the empirically real silver (and not the apparent silver) in its intrinsic nature.

Reply: No. Then the object of illusion and the object of cancellation (or correction) will then be different. Also, there will be absurdity of an object being negated, which did not appear earlier.

Objection by the Dvaitin: If the world is negated intrinsically, then there may not be origination, etc. for the same.

Reply: There is no rule that wherever there is no negation intrinsically of an object, then there will be origination of it. Then only, because the world is being negated intrinsically it may not have origination, etc. According to the Dvaitins, the objects like akāśā (ether) are not negated in their intrinsic nature and yet they are not admitted to have origination. Thus origination, etc., are determined by some other condition namely the nature of the object, etc. which is accepted by us too.

Also this view is not against the view of Prakâśātman, the author of the Vivaraņa, as when viewed along with the interpretation of the above text in the Tatvaprakāśika, we get that ‘the view of Prakâśātman is that the empirically real silver is the co-relative of the negation. This also concurs with the fact that activity of the individual to take it is directed towards what is known as empirical silver. Hence one has to admit that the apparent silver directly appears as identified with the real silver can never be the empirically real silver.

When both the object and the co-relative are represented by similar case endings, the negation (nas) means reciprocal negation or the difference. Thus the sentences ‘Pot is not the cloth’, ‘”This is not silver’ mean that there is difference between them. Thus this (the silver appearing in the shell) is not the empirical silver. This is what we get by this negation. Prakaśātman, when he says that empirical silver which is negated, he means that the illusory silver which appeared as identical with the empirical silver is negated (and not the empirical silver alone). The proof for the acceptance of illusory silver identified with the empirical silver is the fact that the person under illusion was drawn towards it. The negation shows that the illusory silver is distinct from the empirical one. Thus the empirical silver is the co-relative of the reciprocal negation between the illusory silver and the empirical silver. Hence the negation ‘This is not silver’ indicates the distinction between the apparent silver in the forefront of the individual, denoted by the word ‘this’ and the empirical silver denoted by the word ‘silver’. The knowledge of this distinction implies that the apparent silver is false.

But in case the negation is in the form ‘there is no silver here'(nātra rajatam), then the object of this knowledge is absolute negation of silver. In other words, it is the absolute negation of the experienced apparent silver in the locus of its appearance. This is because of the rule that whenever there are different case endings in the words representing the co-relative and the locus of the negation, then absence of association is revealed by the negation. Thus in this case where negation is in the form ‘there is no silver here’ has for its object, the absolute negation of the experienced illusory silver and this absolute negation is empirical in nature. This states the falsity of silver explicitly. Hence the definition of falsity does not lead to any conclusion against the established opinion (apasiddhānta); does not entail the forced admission of a real silver elsewhere (anyathākhyāti) nor does it involve any contradiction of the views stated in the earlier texts.

Objection by Dvaitin: The falsity is then identical with the asat (devoid of any ontological status). It is because the objects like pot etc., are eternally negated in the locus of their appearance and you do not accept their presence at a place other than their locus of appearance resulting in their negation everywhere; i.e. both in their locus of appearance and at other places. Then ‘How does the illusory object differ from the unreal (asat)? The unreality of the horn of a hare is not in any way different from this. The unreality of the horn of a hare cannot be its incapability of being denoted by a word, since it is denoted by the expression ‘incapable of being denoted by a word’. Nor the unreality can be the character of not being cognized. If the unreal object is not cognized then how one can have

(i) the knowledge of difference of unreal and

(ii) the denial of the cognition of the unreal; and

(iii) usage of the word unreal (asat).

Nor can it be said that unreal is one that can never be the object of direct cognition because then the definition of unreal (asat) will be too wide of its application to objects that are not cognized directly by any one like ākāśa, dharma, adharma.

The Advaitin replies to this as: Negation of an object at all places both in its locus of appearance and in other places is common to illusory objects and asat (unreal) objects. But unreality (asatva) is the incapability of being presented in any locus as existent. This does not exist in silver on the shell or in the world prior to its negation. Hence they do not become unreal. Before negation, both the silver in the shell or the world do not fail to appear as real and hence they appear as existent. The fact that the locus of appearance of the false is real, is signified of the word ‘upādhi’ in the present definition of falsity. For śūnyavādins, the illusion is not grounded in a real locus. Hence they cannot claim that the silver appearing on the shell or the world possesses the character of being presented as existent in a locus which distinguishes the illusory object with an unreal.

Third definition of falsity.

This definition is also given by Prakāśātman in his Vivarana. Falsity consists in its being cancelled by knowledge. The author of the Nyāyāmṛta criticizes this definition too. The flaws adduced are:

(i) This definition applies to any cognition that is destroyed by a succeeding cognition. But the preceding cognition is not false. Hence it is too wide;

(ii) Objects like a pot which are false according to advaita too get destroyed by the fall of a pestile (log of wood) etc and not by knowledge. In such places the definition is too narrow;

(iii) Even if character of being cancelled by knowledge qua knowledge is intended then the same flaw as being too narrow in pot etc., will continue;

(iv) If it is the character of being cancelled by the direct realization of the substratum is intended, then it exists in the shell-silver too as it is cancelled by the direct realization of substratum. But the character of being cancelled by knowledge by virtue of its character of being knowledge is absent in it. Hence there results the flaw of the probandum being absent in the example shell-silver (sādhya vaikalya).

(v) If falsity is that being cancelled by knowledge by virtue of its possessing the character which is universally concomitant with the character of being knowledge (jñānatva vyāpya dharmeņa), then the definition will be too wide since it will apply to the mental impressions which are cancelled by the corresponding memories that are universally concomitant with the character of being knowledge.

The Advaitin replies to this as follows: The intended meaning of the expression ‘sublation by knowledge’is the character of being the co-relative (pratiyogin) of a negation which is due to knowledge and which is the negation of the object in all forms of existence both gross and subtle. Each object exists in two forms; (i) in its own form as an effect and (ii) its causal form. This is due to the fact that the effect pre-exists in its material cause.

Even though the pot ceases to exist in its own form as an effect when it is broken by a log of wood, it does not cease to exist in its causal form. The cessation of that pot even in the causal form is due to the Brahman knowledge only. Hence the definition does not fail to apply to objects like the pot not existing in its physical form. Thus the definition is not too narrow and the flaw shown (as ii) above does not arise.

Also the earlier cognition, cancelled by the succeeding cognition continues to exist in its causal form. Thus there is no negation by the succeeding knowledge in all forms of existence. Hence the flaw of proving what is already accepted also does not arise. When objects like ākāśa (ether) are negated by the knowledge of Brahman both forms are cancelled and hence they are proved as illusory. Thus the definition will not lead to proving an unintended thesis. The non-existent objects like the horn of a hare etc are non-existent in all forms; gross as well as subtle. But that non-existence is not due to knowledge and so the definition does not suffer from the flaw of being too wide in its applicability to unreal (asat) objects. Objects like shell-silver have to be accepted as existing at the time of their appearance (since they will not appear if they do not exist). They thus have an ontological status as phenomenal. They are cancelled by the corrective knowledge. Hence the flaw of probandum not existing in the example also does not arise (See (iv) above).

This has been very well explained by the sentence in the Vivarana “Sublation is the cessation of ignorance with what it entails in the potential as well as actual state, by Wowledge”. 15 The author of Vârtika also says “As soon as the valid cognition is generated by the statement ‘That art thou’ ignorance with its effects is understood to be non- existent in the present, in the past and in the future”.16 The sentence ‘along with the effect it did not exist’ is intended to show that the effect of ignorance in its potential form does not exist. Similarly the sentence ‘along with the effect it will not exist’ shows the cessation of the future effect of ignorance. The negation of a future effect on account of something else, i.e., negation not due to knowledge cannot be taken as a cause of sublation. We thus find that the material cause of silver namely ignorance is cancelled along with its effect, in the gross and subtle forms by the direct cognition of its substratum.

Each shell-silver perceived by every individual has a distinct nescience as its material cause. Hence the probandum is not absent in the example. Every one accepts that after the knowledge of substratum, the ignorance of shell as well as the silver over it does not exist like the pot after it is broken by a log of wood. It is also right to say that falsity consists in being cancelled by knowledge in its capacity of possessing a character which is universally concomitant with the character of being knowledge (jñānatva vyāpya dharmeņa jñāna nivartyatvam). This is because the cessation of prior knowledge by a succeeding one is not by the knowledge as shown above but by being a special quality of the Self that arises immediately after it. (udīcya ātma viśeşa gunatvena). Thus there is no flaw of proving what is already accepted. Nor is the definition is too wide, as it applies to the mental impression not cancelled by desire etc but cancelled by memory.(v. above). There is no proof that mental impressions are cancelled by memory in the capacity of memory. On the other hand experience confirms that birth of each memory strengthens the mental impressions. The strength of mental impressions is to have many of them corresponding to an object. Thus the definition is flawless. However, the definition of falsity could be the character of being cancelled by the direct realization of the substratum. Then all the flaws shown above will have no place at all. Nor there is no flaw of being too wide, in its application to the doubt when it is cancelled by knowledge acting in its capacity of certitute (niścaya) which is universally concomitant with the character of knowledge (jñānatva vyāpya dharmeņa). Thus the third definition is also flawless and thereby proves the illusory nature of the world well

1. jñātvā devam mucyate sarva pâpaiḥ. Śvetâśvatara Upaniṣad 1.11

2. ‘jñânâgniḥ sarva karmāņi bhasmasât kuruterjuna’ – Bhagavad Gītā 4.37.

3. ‘âtmāvāre draşțavyo mantayo nididhyāsitavyah’ – Bṛhadaranyaka Upaniṣad (hereafter BU) 2.4.5

4. Advaita Siddhi-N.S.Anantha Krishna Sastry-Parimal Publications Delhi 1997. P.4

5. BU.4.19

5. Mundaka Upaniṣad.2.8.

6. Mundaka Upaniṣad.2.8.

7.BU.4.3.10

8. BU.3.4.2

9. BU.4.5.14

10. BU.3.4.2

11. Māndūkya Kārikā 1.18.

12. Taittīrīya Upaniṣad.2.5.4

13. Pañcapādikā Vivaraņam p.106. S.Subramanya Sastr Mahesh Anusandhana samstan, Varanasi

14. BU.2.3.6

15. Vivaraņa p108, S.Subramanya Sastri, Mahesh An Samstan, Varanasi, 1992

16. Vārtika, 1.1.83

Dr. Goda Venkateswara Sastri

THE ONE AND THE MANY ACCORDING TO THE PARAMĀCĀRYA

This world, particularly the present generation, is really blessed to have Śrī Candraśekharendra Sarasvatī, the sixty-eighth pontiff of Śrī Kāñcī Kamakoți Śańkara Matha in our midst till the recent past. The Upanishad proclaims that “one should adore the knower of the Self”. ¹ People in general are aware of the teachings of the scriptural texts, but not of the person who followed their teachings and lived accordingly. When such a person comes truly, he is an avatāra or incarnation of the Divine like that of the famous Rāma and Kṛṣṇa in India. The whole world was attracted by the Paramācārya’s simplicity, profound analysis, boundless mercy, and concern for the individual. This essay is a small garland of flowers made mostly from his views and sayings at different times and offered at the holy feet of the Paramācārya.

That there is one source for all the myriad objects is intuitively known to everybody. If it is accepted that there is creation of the universe, then there must be a cause for it. That cause or source is generally termed as the Divine in almost all the religions. Beings, animate and inanimate, are created by the Divine. After creation they must be sustained, lest there is no meaning for creation. Also, existing things should give way for things yet to come. If not, there can be no way for improvement. That takes us to destruction. Unless the old is destroyed, a new thing cannot come in its place. Thus, in all religions the Divine is said to be the creator, sustainer and annihilator leading to the birth of the universe and deluge at a certain period of time. The Vedas too have formulated the concept of the Divine which is called Brahman-Brahman from whom all the worlds emanate, on whom they sustain and unto whom all get merged2. Now a doubt arises whether Brahman is one or many. What does it matter, one may ask, if the creator is not a single entity? What is wrong to accept a team or a well-knit unit looking after the execution of all these activities? These thoughts caught the attention of the ancient thinkers called Rșis, and they came out with a solution considering all the possibilities. In the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad, an inquiry was taken up about these questions: “What is the cause? Is it Brahman? Where from are we born? By what do we live? And on what are we established? O, ye who know Brahman, please tell us about how we manage to live our different conditions in pleasures and pains.”3 The Upanishad seers also considered the questions about time, nature, fate, chance, the five elements, the individual soul, etc.4

The very existence of Iśvara, the Creator was questioned and many inferences were formulated to prove the existence of God by Udayanācārya in his famous work, Nyāya-kusumāñjali. The Mīmāmsakas, however, had different views on this problem. Some thought that this world is permanent and does not undergo any change. However, they accepted the Godhead sans any physical form. Whatever it is, the creation of the world is also an act; for, the performance of an action requires a doer or an agent; that is to say, one should possess (i) the immediate knowledge of how to perform an act; (ii) the desire to perform it; and (iii) actual performance of the act. That the Divine (Brahman) has all these, is given by the scriptural texts.

The śruti text, “He who is all-knowing and all-wise, whose austerity consists of knowledge, from Him are born this Brahmā (Hiranya-garbha), name-shape, and food,”5 vouches the existence of immediate knowledge to the Creator. It is further stated that the Creator-God “desired: Let me become many, let me be born…6” Again, the scriptural text which says: “He produced the mind”7 is the proof for the existence of action in Brahman. Thus, on the authority of the scripture we have to say that Brahman is the cause of the universe. When we say “cause”, there arises a problem whether Brahman is the efficient cause or the material cause. In our day-to-day experience, every object has a material cause and also an efficient cause. For example, a pot has clay as its material cause, and a potter as the efficient cause. To take another example, a cloth has threads as its material cause and the weaver as efficient cause. In general, only inert substances are material causes, and sentient beings are the efficient causes. In the light of the examples mentioned above, one may argue that the efficient cause of the universe may be the sentient Brahman, but the material cause must be some inert substance. But the Upanishads and the Sūtrakāra hold that Brahman alone is both the efficient and the material cause of the universe8. This view made the Vaiśeşikas, the Naiyāyikas, and the Sankhyas search for a material cause for the universe.

If we take a substance and split it into smaller particles, we will finally arrive at the smallest particles called the atoms, which are not divisible at all. The Vaiśeşikas and the Naiyāyikas thought that the Creator-God, by his volition, combined two atoms to form a molecule, and then combined three molecules to produce a triad, and so on. It is through this process of combining the atoms and the molecules, the entire universe consisting of various kinds of objects was produced. These philosophers applied the same logic with regard to the elements such as water, fire, and air. They thought that ether (ākāśa) was eternal, and so it has no atoms.

The Sänkhyas were not satisfied with this theory. They undertook the inquiry from another perspective. Any object in the world has three roles to play with reference to human beings. A human being sometimes gets happiness by seeing an object; sometimes the same may be a source of misery to him. At some other time, he may just be indifferent to it. The same object giving happiness to one at a period of time may be a source of sorrow for another. Some other person may not be bothered by it at all. Consider the following case: one and the same body of a woman generates happiness, misery, and delusion to her husband, to co- wives, and a lover, respectively9. It means that every object is made of three guņas, which are the causes of these three emotions. As every object in this world has these three guņas, its material cause too must contain all these three constituents. So, from this experience, the Sankhyas draw the inference that prakṛti, the primordial cause, is the source from which the world is generated. They also thought that prakṛti, by its innate nature, spontaneously transforms itself into various objects of the world in a particular order. Just as a cow spontaneously generates milk for feeding the calf, just as water flows from a higher level to a lower level, even so prakṛti undergoes change and evolves into various objects in order to generate the experience of pleasure and pain to the jīvas. 10